Have you watched Russian Doll yet?

It’s only eight, half-hour episodes. Extremely bingeable. Have you watched yet? In case you haven’t the in-depth, spoiler-laden review will be coming next week, giving more people a chance to see it. For now, let’s just talk about Russian Doll as an achievement in allegorical storytelling. The Groundhog Day-style narrative could have just been a gimmick, a way to spruce up a hangout comedy about a birthday party, but it turns out the time-loop structure is integral to Russian Doll’s theme, which is about confronting trauma. After seeing the trailer, I wondered if the comparatively small creative pool making the show would make a palpable difference in its outcome, and I think it does. Russian Doll is consistent in a way that only a very specific vision can be. This is a show that never loses sight of its story, avoids tangents, and, despite being set in New York City and featuring a number of interesting supporting characters, is really only about two people.

One thing Russian Doll makes very clear is that Natasha Lyonne rarely gets material that is good enough for her. She is wonderful as Nadia, a caustic thirty-something who might have a death wish. But it’s not just that her performance is perfectly suited to her rapid-fire delivery, it’s that Nadia is a whole person, and Lyonne gets to play not just a comic relief gal pal, or sidekick, or a sort of loud-mouthed version of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Nadia is a walking callus, and Lyonne gets to show the moments that pierce her, and she gets to do it without descending into stereotypical histrionics.

There’s no big epiphany scene, no monologue pulling it all together for the audience. Nadia is struggling, but her struggle isn’t the sum total of her character or experience. We get to see bits and pieces of Nadia as she cycles through the same night over and over, and through it all Lyonne plays Nadia as someone who has learned to live with her damage so well that she doesn’t think she’s damaged. It’s a two-tone performance, because not only must Nadia be convincing to us, the audience, but also to herself within the show. Lyonne captures all of those shades and nuance and makes it look so easy you’d swear she’s not even acting.

And then she directs the final episode, “Ariadne”. This is only Lyonne’s second directing project, following a short film, and she immediately establishes herself as a very capable and interesting filmmaker. A lot of actors turned directors will move the camera a bunch just to prove they know what a camera is and how it works. Lyonne’s camera moves almost constantly, and she sets up a lot of fancy shots, but all of it is integrated into the story of Russian Doll. As everything starts converging, those fancy splits and angles aren’t just for aesthetics, they’re working to underscore the story and emphasize particular character moments. It’s extremely well structured, and just as the narrative builds up layers, the cinema of Russian Doll starts piling up these different techniques, too.

The other seven episodes are split between series co-creator Leslye Headland and Jamie Babbit, and the way Lyonne jumps off what they have done in the final episode is really fun to watch. If you haven’t yet, you should really watch Russian Doll. It’s a trip. Watch for Natasha Lyonne’s and Charlie Barnett’s performances, watch for the excellent direction, particularly what Lyonne does in the final episode, and watch for the twisty narrative that turns out to be one of the most effective allegories in recent memory.

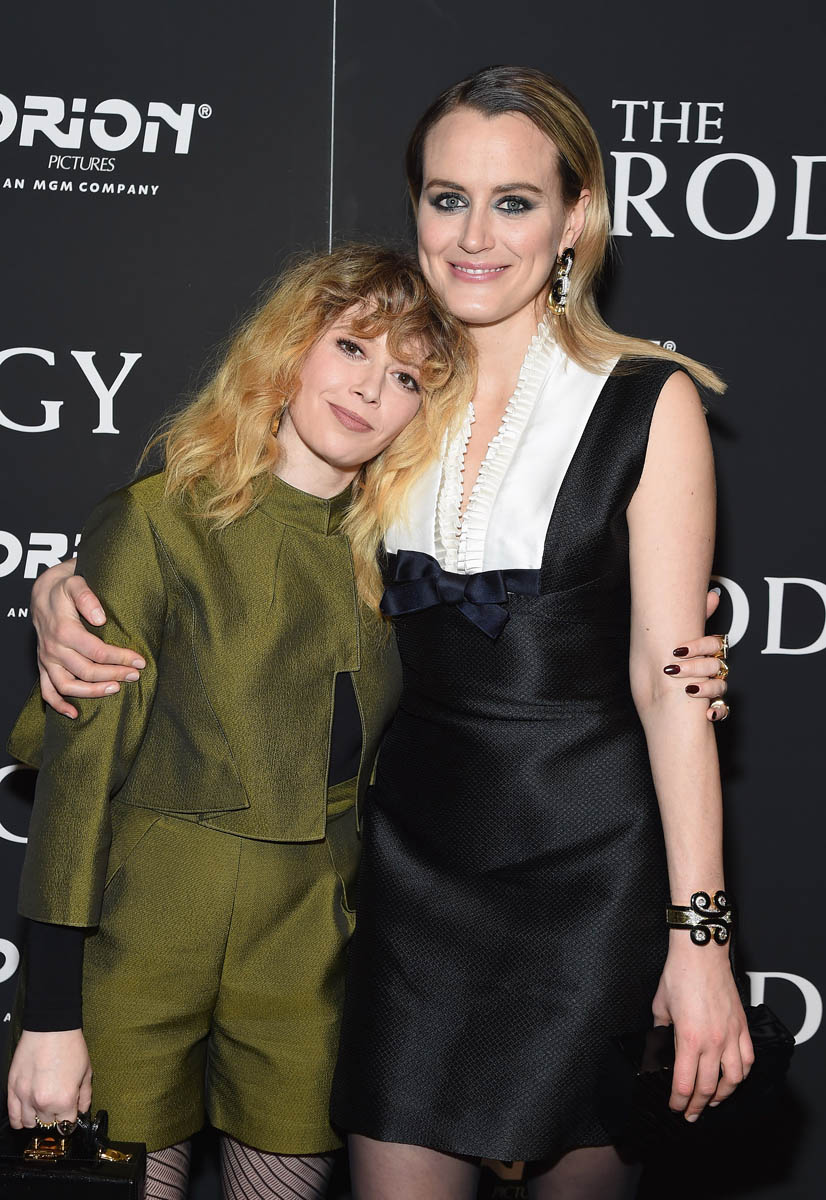

Attached - Natasha Lyonne at a screening of The Prodigy in New York City with Taylor Schilling.