Questlove and the price of Black excellence

Once again, musician and Oscar-winning filmmaker Questlove is reflecting on a struggle that exists in the undercurrent of the lives of Black people, but is rarely articulated. It’s not the well-known concept behind the idea of the “Black tax”, and it’s not the impact white privilege has had on Black people. Instead, it’s the pressure he and so many others have faced in wanting to intervene when their Black counterparts experience some sort of downfall.

In his new documentary, SLY LIVES! (aka The Burden of Black Genius), Questlove’s focus is on Sly Stone, a funk musician that led the Sly & the Family Stone band in the 1960s and 70s. He looks at the toll that fame and success had on Sly who, despite being sober now for nearly a decade, experienced substance abuse issues as a result of his time being in the limelight. The film seeks to answer the question of why we self-sabotage in the first place.

Questlove dives into how Sly’s self-sabotage began, which ultimately came from being “the chosen one”. As a musician, Sly had initially created a masterpiece of an album called A Whole New Thing, but the intellectual genius behind it made it hard to digest for people who, really, just saw Sly as a person who could make them dance, leading him to feeling like the intellectual component of his art was being rejected.

"Look, you're doing way too much. You got to simplify it. People aren't as smart as you are. Like, instead of you being the smartest guy in the room, be a relatable guy in the room. People just want to dance to the music," Questlove said, paraphrasing the messages Sly was receiving from labels and fans at the time.

Decades later, we’ve seen this same attitude manifest, holding strong over how Black people “perform” in society. This is the same message LeBron James got from Fox News host Laura Ingraham when she told him to “shut up and dribble” back in 2018 after he spoke about politics, which prompted a series of epic responses from him, including the move by his company, Uninterrupted, Inc. to trademark the four-word insult, as well as a three-part documentary series on the evolving role of athletes in political discourse in America.

It’s also no different than Colin Kaepernick being iced out of the NFL for taking a knee during the national anthem. At the core of this ongoing attitude toward Black people is that we are entertainers and athletes first, and human beings second, if at all. We are here for entertainment purposes only.

“One of the burdens of Black genius is sometimes, like, the burden of being white people's favorite Black person. That's, like, a mark of shame like, ‘Man, I gotta get right with my people first before the rest of the world loves me,’" Questlove said, reflecting on the initial warm reception Sly received from his white audience.

Upon the rejection of A Whole New Thing, Sly felt prompted to go on to, in a “sarcastic, bitter middle-finger type” of way, begin making music that people clearly wanted. And he did it in a way that was a nod to his Black audience, adding “sarcastic” elements of funk, becoming the first artist to use a drum machine, laying the foundation for artists like Michael Jackson and Prince to build off of years later.

The amount of nuance and consideration Sly had to navigate in his career as a musician still rings true for a lot of Black people in their respective industries. Whether one is in art, finance, healthcare or tech, the pressure that Sly faced to be palatable still exists. And with it comes the pressure Questlove is describing, of wanting to help ensure others are palatable, too; the pressure to intervene whenever we see someone that looks like us at risk of a downfall.

During a Q&A for the film, Questlove reflected on the breakdowns he’s seen from several musicians he’s worked with during their journey to success.

“The thing is, it's very jarring that 11 people that I've worked with in that studio, there's always a sabotage, panic, career-ruining moment that happens with them,” he said, before going on to add, “I often wish I could have an intervention talk.”

Entering into the media space during my final years of university, I was ushered into the industry by Black women who held my hand. They pulled me aside, offering one-on-one mentorship, sent me messages letting me know what to say and how to be. I was advised not to stand out too much, and simultaneously warned about the dangers of being too bland. It was a daily balancing act that at times consumed all my energy, leaving very little of it to be creative – a struggle I didn’t feel my white counterparts having to navigate.

Years later, as a more established career woman who’d spent years paying it forward and mentoring other women of colour, I find myself exhausted at the idea of doing it anymore. When young women reach out wanting advice, hell, even time, I am guilty of leaving the messages unread. The cocktail of guilt, shame and burnout is best likened to that scene in Titanic where there are only so many lifejackets and lifeboats to go around. Am I just a greedy bitch who got lucky enough to end up with the tools I needed to survive? What about everyone else that got left behind? They’ll figure it out, right?

Maybe. But maybe not. As I wrote last week, the world is not kind to Black professionals, particularly women. And rather than be a source, a guide for how women can navigate the impossible terrain of feeling the need to code switch, not speak up too much over fears of feeding into stereotypes, dealing with microaggressions, all while being unfairly compensated, the guide and source I was lucky enough to have in the early days of my career, my gas tank is empty.

“It's that level of pressure that one puts on themselves. And there's just no space for humanity in entertainment, but especially in Black entertainment.”

Questlove is describing the myriad of emotions that exist, all while trying to be creative, to be professional, to be an active, contributing member not only in our place of work but also in our families, our social circles, and our society. And while, regardless of skin colour, we all deal with some degree of push and pull, Questlove’s story, along with the story of his creative counterpart from decades prior prove that the needle is moving, but not nearly enough.

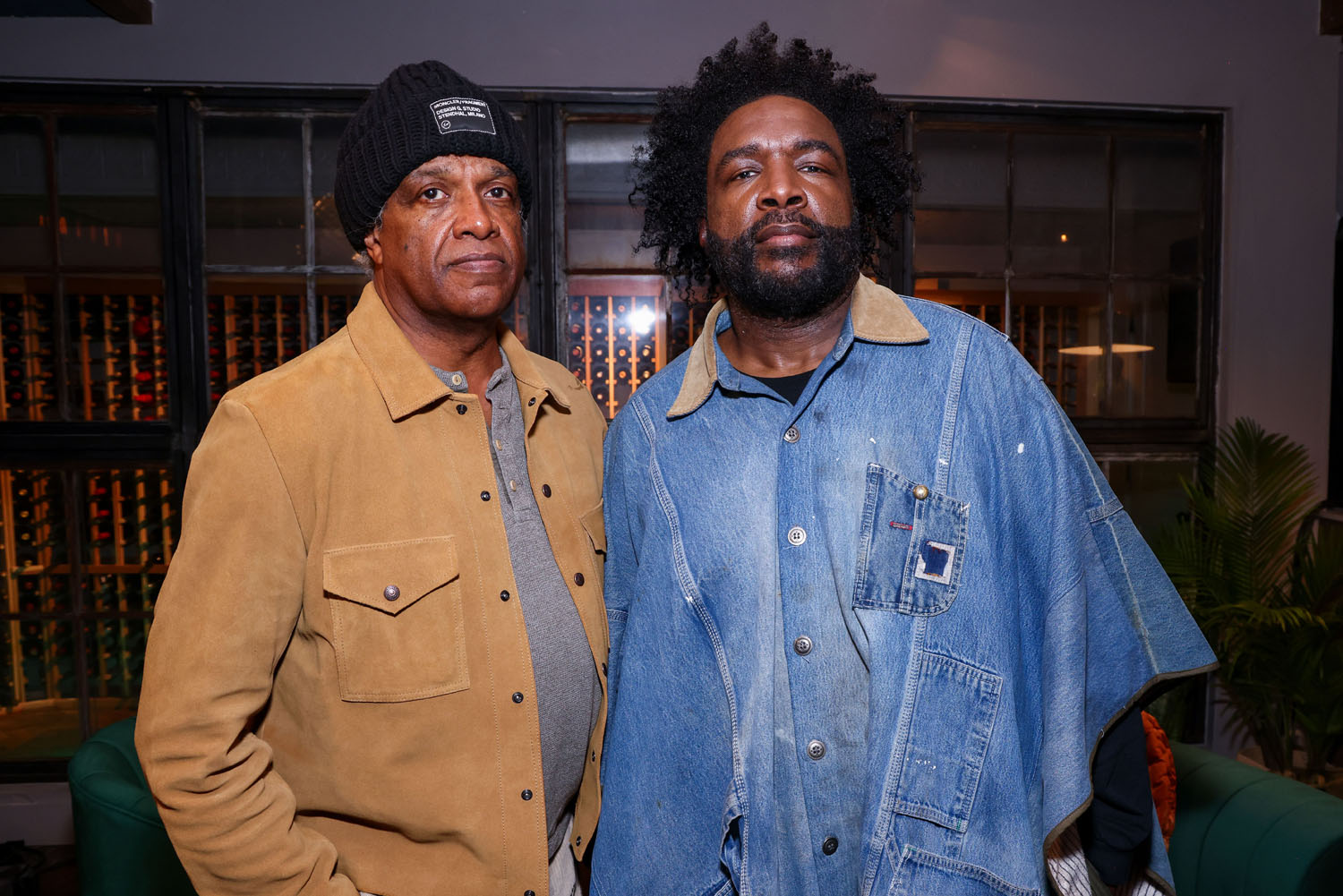

Here's Questlove last month at Sundance.