Reframing Cancel Culture

(This is the latest installment in our Long Read series. For previous entries, please visit the Long Reads archive.)

Yesterday morning, Harper’s Magazine published a letter written and signed by 50 public figures including J.K. Rowling, Malcolm Gladwell, Gloria Steinem, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and so many more. The letter condemns the concept of public shaming for “weaken[ing] our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favor of ideological conformity”. Although never explicitly mentioned, it can basically be read as a condemnation of “cancel culture” in the wake of protests and calls for reform.

Rowling, you’ll remember, faced backlash for both posting and defending her transphobic tweets and views. In 2016, Margaret Atwood was criticized for her support of a letter that demanded that the University of British Columbia provide reasons for firing one of its instructors after an accusation of sexual assault. Ironically, Atwood was trending this week for seemingly calling out transphobes by sharing an article about the spectrum of biological sex.

https://twitter.com/pylonfan/status/1280436769985617925?s=20

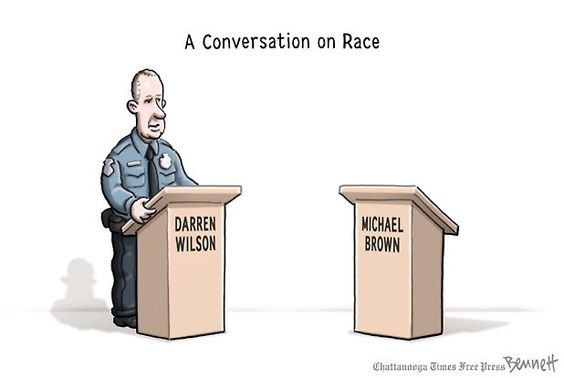

Obviously, the letter was supported by many people. But there were many others who called out its misguided direction and oversimplification. The one line that sticks out to me is, “the way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion, not by trying to silence or wish them away.” That’s definitely why the world erupted in protests, right? Because the exposure, argument, and persuasion that Black lives do indeed matter was going over so well with everyone?

Like many people who decry the disintegration of free speech, it completely ignores the socio-political contexts in which these conversations take place.

The argument also grossly overstates the impact something like cancel culture has on someone’s right to free speech. Everyone is free to share their opinion. It doesn’t mean that people have to like it, support it, or even engage with it. No one has taken away J.K. Rowling’s platform. Some of us have just agreed that what she says is sh-t.

This letter is part of a much larger idea that has been floating around in my head for a while, but especially in the past few weeks. In the wake of the protests, many people have been “cancelled” and have had to own up to their anti-Black racist actions, especially those in the past. Last week I wrote about Shane Dawson, and two days ago Cody wrote about Terry Crews’ unnecessary defense against the myth of Black supremacy. Even in the past few months, people like Ellen, Doja Cat, Camila Cabello, and Lea Michele have all been cancelled.

But what does it mean to be cancelled? I don’t think most people have a clear definition. For some, it’s a boycott - of their music, their movies, and their work. For others, it’s a hashtag. I see a #SoAndSoisOverParty trending every week. In its simplest form, cancel culture is public humiliation. For people who rely almost entirely on the support of the public, the idea is that being cancelled can result in an experience that hopefully leads to atonement and correction for the injustice for which the person was cancelled. It’s a reckoning for people who aren’t normally held accountable for a lot of the things they do.

What I’m interested in exploring is what happens after someone is cancelled. Can they come back? Should they even be allowed to? When I originally conceived of this piece, I wanted to do a deep dive of cancel culture. It was going to be about whether or not we should cancel people and what the main arguments of both of those sides were. But we’ve already had those conversations.

Vox wrote an incredible dissection of the issue, including tracing it back to its roots in the Black Civil Rights movement. According to Vox, cancel culture was the modern version of the boycott and bubbled up into the mainstream through Black Twitter. Time Magazine’s Sarah Hagi wrote about the power that cancelling has to give voice and power to people who historically haven’t had it. Even The New York Times has weighed in, writing a sort of “Cancellation 101”.

I highly recommend reading all of the above. Each piece encourages a nuanced conversation about a subject that can be so incredibly polarizing and emotional. Those who are against it point to its ability to shut down discussion and its oversimplification of often complicated circumstances. Those for it see it as a tool for the masses to hold those in power accountable in the only way they can. And after going back and forth for half a decade, you would think that we would have come to some sort of conclusion.

Yet here we are in July 2020 talking about cancel culture. And it has somehow become even more polarizing. So rather than examining cancel culture, I want to reframe it through the lens of celebrity gossip, because that’s what we do here at LaineyGossip.

In today’s world, cancel culture has now become part of the celebrity ecosystem. As long as social media exists, and as long as we continue to pay attention to what celebrities do, there will be cancel culture. That last point is important too. Cancelling someone by very definition means that at some point they were scheduled. The power and privilege that celebrities have comes directly from the people who support and love them.

At its core, this celebrity-fan relationship is built on trust. We trust that they will entertain us, maybe even that they will represent us, and that their lives are something that we can learn from. This is particularly evident whenever someone gets cancelled because you’ll see immediate tweets all like, “[this celebrity] is cancelled, but thank god [other celebrity] is unproblematic.” The idea of the “unproblematic fave” or “the only white man I trust” belies that we have a deep belief that the people (or at least the image we have of them) we prop up onto these public platforms will use them responsibly.

When someone breaks that trust, people feel betrayed and disappointed. And once that trust is gone, the whole relationship disintegrates, which is why they’re cancelled. Which means that even if someone maintains commercial success or retains their platform, their social capital and impact are lessened. It’s why even years after someone is cancelled, it continues to come up.

We’ve already established that cancelling has little impact on someone’s career, especially the more powerful they are. I mean, Prince Andrew is literally in a picture with a woman who has accused him of sexually assaulting her when she was a minor, and he still gets to decide whether or not to golf in Spain this year. Very often, audiences don’t have the same power to administer real consequences. But as the NYT article explains, cancelling is “ultimately an expression of agency.”

This idea of trust might also explain why cancelling has grown in the zeitgeist. Have you ever been in a relationship where a lack of trust f-cks up other relationships? Over time, we’ve become more suspicious of celebrities, expecting a downfall to be right around the corner or carefully examining their apology to see whether they’re actually sorry or they want to save face.

So back to my original question. Looking at it from this angle, how does one return from being cancelled? Well, just like when someone breaks our trust in real life, it depends. There’s the severity of the breach, the frequency with which it happened, how long ago it happened, and whether or not someone has grown since. Ultimately, people have to work hard to gain back a person’s trust and they have to prove time and again that they changed.

Even still, the unique part about looking at this issue from a trust standpoint is that it acknowledges that there will always a small amount of mistrust. I want to use a Lady Gaga and Beyoncé quote from "Telephone" as an example because it perfectly encapsulates what I’m trying to say. Also I’m gay.

“You know Gaga, trust is like a mirror. You can fix it if it’s broke…”

“...but you can still see the crack in that motherf-cking reflection.”

It’s that crack in the mirror that outraged people when Kevin Hart explained that he was tired of having to apologize. There was more to the story, but at its core, people were mad that he confirmed what we were thinking: he wasn’t ever sorry in the first place.

Therein lies the key to who should and shouldn’t come back from being cancelled. It’s the desire to grow, change, and to do better. It’s the vulnerability of admitting when you’re wrong and trying to learn from it. It’s being open to criticism and taking responsibility for the hurt that you’ve caused.

Because cancel culture isn’t about preventing people from making mistakes. That’s frequently an argument used against it, but it’s ill-informed. Cancelling really is about getting celebrities to see the consequences of their mistakes, an important part of the learning process. If you never see any backlash for your actions, how are you going to know if they’re bad?

When it comes to celebrities and famous people, it’s hard to know what’s going on in the background. Which means that while I want to believe that everyone who apologizes truly means it, we know from experience that that isn’t true. How can we tell if someone has actually grown and put in the work? It’s hard. Years and years of a lack of accountability have made famous people feel entitled to their fame and fortune. It’s made men like R Kelly and Harvey Weinstein feel as though they’re above the law.

I think that’s maybe why the bar is set so high for people. If the public is going to be convinced that you’ve changed, they’re going to need a lot of proof. And by now, celebrities know that. Remember when they taught us in school that everything you put on the internet is forever? I feel like people never truly understand how important that piece of advice is. Today’s celebrities should know that cancel culture is an occupational hazard. That having to answer for your present and past behaviour is on the job description of being really famous.

Are there cases where it goes too far? Of course. But completely writing off cancel culture as a threat to free speech does a great disservice to the conversations it forces us to have. Ironically, the letter that J.K Rowling and so many others signed ignores all that nuance. By lamenting the oversimplification and emotional reaction intrinsic in cancel culture, they’ve oversimplified and emotionally reacted to it themselves!

Perhaps we need to shift the way we view what cancelling looks like. At the centre of this issue is a discussion about the kinds of people we choose to put our trust in, and whether they continue to deserve that trust. The past few weeks have been the “Facebook Friend Purge” where we really consider whether those with fame are responsible enough to have it. And in doing so, there’s an important conversation about how those people have looked and acted a certain way for most of history.

I think the fact that we even have the ability to do this and to hold people accountable is incredible. It’s like a class action lawsuit. There’s power in numbers. Cancel culture took away Roseanne’s show. It brought to light the atrocities of Harvey Weinstein. Even yesterday, it made Halle Berry reverse her decision to play a trans character in a movie (and if you don’t understand why that’s important, watch Disclosure ).

It is not true that cancelling is always final. While it’s possible to recover, the work involved emphasizes how fragile but important that trust is. Even with its flaws, if cancel culture makes someone think twice before hitting that tweet button, maybe that’s not such a bad thing?