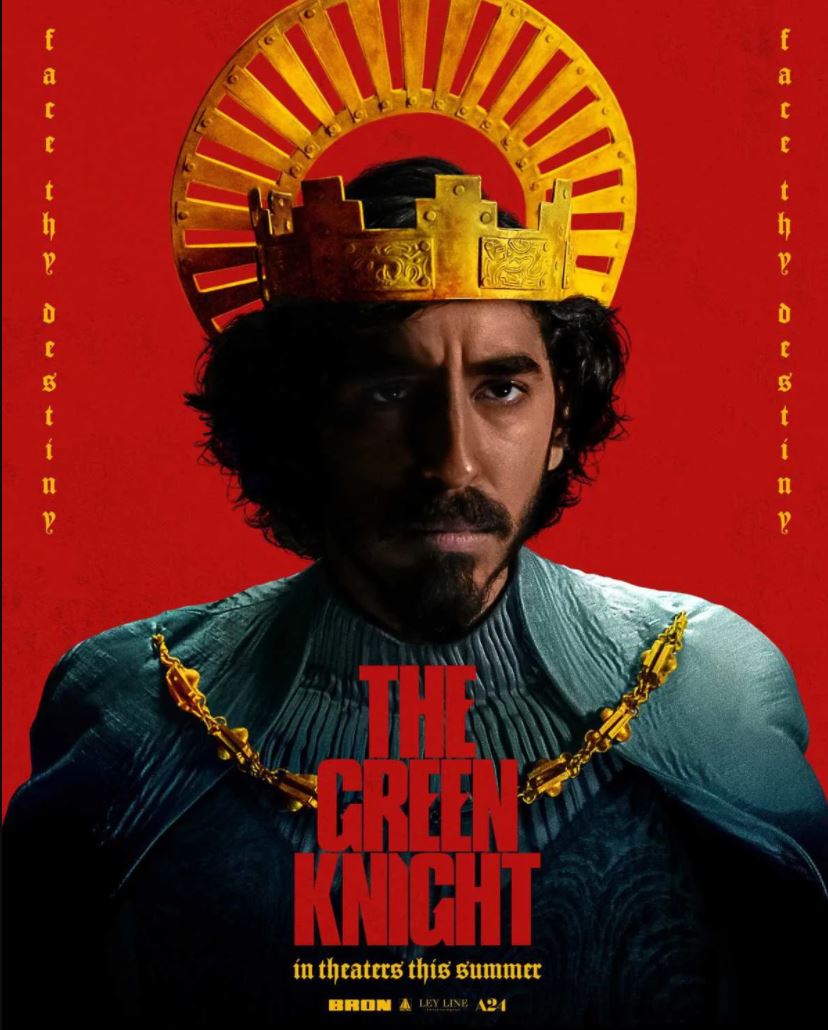

Dev Patel in The Green Knight

David Lowery is a filmmaker profoundly interested in time. All of his films from the traditionally narrative (The Old Man & the Gun) to the abstractly lyrical (A Ghost Story) to the big-budget studio (Pete’s Dragon) in some way address time, its relentlessness, man’s desire to defeat it, man’s incapability of defeating it, and that sense that on a long enough scale, all of this comes back around again. Lowery is also interested in place, though, specifically the places that bind us to the earth and to Earth, and the ways in which our metaphysical selves may manifest in places long after we are gone. The Green Knight, Lowery’s loving if freely adapted retelling of the Arthurian legend Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, tackles both time and place in ways that are recognizably of Lowery in the 21st century and of countless unnamed bards singing stories of gods and monsters to people who have long since disappeared into the ether of time, but who still survive through these stories.

Lowery, who writes, directs, and edits, is loose with his retelling of Sir Gawain’s story. Here, Gawain is reimagined not as merely a young squire in King Arthur’s court, but as the king’s nephew, son of Morgana le Fay, and is not the chivalrous image of purity and piety presented in legend but a more modern disaffected youth, wasting his time in brothels and bars.

Played by Dev Patel, Gawain is in the shadow of his powerful uncle and mother, untested and untried, too young to have been around for the great battles of the king’s own youth. Lowery ditches the proper names, presenting the court as simply “the king” (a grizzled Sean Harris), “the queen” (Kate Dickie), and “Mother” (Sarita Choudhury), but the king and queen sit at a round table, and the court falls silent when the king draws his sword. Mother, meanwhile, engages in a bit of magic on Christmas day, the first of many instances of Lowery smashing early Christianity against pagan symbology (I could write a whole thesis about the presentation of Guinevere in this world, and how Lowery hints at her pagan roots as the Welsh triple goddess Gwenhwyfar).

When the king asks Gawain for a story of himself so that the king “may know of him”, Gawain has no response. He has done nothing of note, and shame is plain on his face. Patel captures all of Gawain’s angles, from his bravado and eagerness to prove himself, to his cowardice and weakness and the flashes of goodness that pop out with a little prompting. Traditionally, the Green Knight comes for Arthur and Gawain intercedes, but in this telling, Mother calls upon the Green Knight (Ralph Ineson) to challenge her son to rise to the occasion—any occasion—since he has nothing to do other than spend time in the brothels with the cute Essel (Alicia Vikander, in the first of dual roles). That time is wasting is implied from the king’s fading physical strength to Mother’s impatience that Gawain make a name for himself before it’s too late. Gawain does so, accepting the Green Knight’s challenge and playing the “beheading game”. Having severed the Green Knight’s head, Gawain must face that entity again in one year and receive the same blow back upon him.

As Gawain travels to the Green Chapel the next Christmas, he encounters a land of magic and depravity. Lowery envisions a mythical England being leeched of its magic, as men wage war and breed more cruelty into the world, giants pass in solemn procession into the literal mists of time, and the loss of something strange and wonderful is palpable. Gawain encounters robbers, ghosts, and talking foxes, but it is at the home of The Lord (Joel Edgerton, having a helluva year) and The Lady (Vikander, again) that Gawain encounters another strange time paradox. Their castle is noticeably grander, more architectural, more modern than any structure seen before, and The Lady has a pinhole camera. The Lord speaks of coming and going as a disappearing act, and they seem particularly untethered to place and out of time, more so than anyone else Gawain meets along the way, even the ghost.

Here, Gawain faces physical temptation, brushing up against boundaries the chivalric code does not mess about with, and Lowery also presses the latent homoeroticism of Gawain’s encounter with The Lord. It’s easy to imagine Gawain giving a better account of his actions with The Lord and The Lady, but in the moment, he is weak, imperfect, rude, and Lowery, along with cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo, seems to love framing Dev Patel as an object of natural beauty like the forests and cliffs of Ireland, while having him perform cowardice, fear, cravenness, drunkenness, pridefulness. We only occasionally see the better sides of Gawain’s nature—the courage and resolve that may yet come to define him—but they do appear enough to suggest he could be a great knight, in time, if he can jettison the performative masculinity he’s picked up at court. Gawain is at his best when he is humble, not when he is trying to be what people expect a knight to be.

The Green Knight trips along in chapters made up of side quests Gawain picks up along the way to the Green Chapel, a sort of relapsing narrative that honors how these old legends grow over time, with a thousand retellings and variations along the way that get grafted to the narrative trunk. The uniting element, besides Gawain, is that notion of time and place as things that exist at once outside of us and because of us. Even in his own time, Gawain’s story is being told before it is complete, that his head will be lopped off by the Green Knight a foregone conclusion. Lowery plays with this expectation, inserting alternate endings for Gawain along the way that only add to the sense that this is a story built over time, which has shifted and changed as each new generation repurposes it. We cannot touch time, but in a way, what Lowery does in The Green Knight is make time tangible, anchoring this legend in a modern context. Seven hundred years ago, people gathered to hear of Sir Gawain, just as we gather (safely, six feet apart) to hear of him now. Almost certainly, there were whole generations already devoured by time who knew Sir Gawain’s name before those 14th century Welsh folk did. We can never know them, they can never know us, but we all know Gawain.

The Green Knight is now in theaters and will be available for one day only through A24’s screening room on August 18. From August 19, it will be available to rent on all digital platforms.