The Queer History of Camp

After months of waiting, the Met Gala is finally here, and I am dying to see this year’s outfits. The theme is based on Susan Sontag’s seminal 1964 essay, “Notes on Camp”, in which she tries to explain and describe the sensibility known as Camp. Trying to define Camp is like trying to see who’s on screen during the Battle of Winterfell. You can kinda make out what’s going on, but you’re never really sure what’s actually happening. Sontag even says herself, “Camp is esoteric… To talk about Camp is therefore to betray it.” There is only one rule of Camp. Don’t talk about Camp.

Reading about Camp is like watching an episode of the Twilight Zone. It’s a mindf-ck that both makes you feel like the smartest person in the room and the biggest idiot in the entire world. Everything seems to be camp, although there are some things that are definitely NOT camp. Camp is different from kitsch and carnival. Unintentional Camp is better than conscious Camp, unless you fail at trying to be Camp in which case it’s even better. Here’s some of the gems I read from “A Fugue on Camp” by Allan Pero:

“Camp is a midwife in the birth of melodrama.”

“Camp is the embroidery of nothingness.”

“Contrary to popular belief, camp is not hysterical, but hilarious.”

Even Sontag says some pretty paradoxical things:

“Camp is art that proposes itself seriously…”

“The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious.”

For a sensibility that relies on largesse and boldness, the distinctions are incredibly subtle, which is often why it’s hard to grasp what Camp is about.

If you want to learn about Camp, here are some great resources:

Notes On “Camp” (Full Text)

Camp, the theme of this year’s Met Gala, is almost impossible to define. Here’s our best effort – Vox

What is Camp? Allow These Artists, Performers, and Pop Culture Experts to Explain – W Magazine

For the purposes of discussing it, we can roughly categorize Camp as the appreciation and delight of frivolity, parody, and extravagance. Camp is about artifice, theatricality, and performance. Balls to the wall. It’s an appreciation of something so awful that it’s good, depending on the intention, of course. The Room is a great example. Despite being one of the worst pieces of cinema, it was made with such serious intent and purpose that its over-the-top acting, ridiculous plot, and extraneous scenes add to the Camp factor. Most of the articles describing Camp rely on examples; its easier to identify but harder to explain. It’s like how I’m attracted to Nick Kroll dressed as Liz on Kroll Show. I don’t know why, I just am.

At least in the West, Camp has a definitive queer history. (Important to note: most of the Met exhibition focuses on the white history of Camp, largely ignoring the contributions of black Camp and Camp in other countries. Bollywood is the epitome of Camp!) The most formalized beginnings of Camp come from 17th century France in the court of Louis XIV. Louis XIV was extra af. He invented ballet (which gets a shout-out in Sontag’s essay) so that his servants would move more gracefully around him. He also is credited with popularizing high heels, especially those with red heels (eat your heart out Louboutin), and even created a law preventing others from wearing heels higher than his. Paris became the centre of art, fashion, taste, and décor through his efforts, a status it has largely kept. He was even responsible for winter and summer fashion seasons that we have today!

Louis XIV probably wasn’t gay, seeing as he had several mistresses, but his brother, Philippe, Duke of Orléans, was a different story. Philippe was a gay Camp icon, known for his DiCaprio style partying, and his effeminate tendencies. He was interested in women’s roles, wearing extravagant clothing, bracelets, rings, and jewels, and despite being a courageous warrior, he worried about sun damage to his skin on the battlefield.

French Camp became the fashion of the English court, and these “dandies” or “macaronis” (which is where we get Yankee Doodle from) would dress up and wear makeup. Camp was more directly associated with homosexuality thanks to its proud mascot, Oscar Wilde. Oscar Wilde lived and breathed Camp. Sontag quotes him several times in her essay:

“One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.”

“To be natural is such a very difficult pose to keep up.”

The overt queerness of Camp is reflected in the 1909 Oxford Dictionary definition, “theatrical, effeminate or homosexual.” Throughout the early 20th century, gay icons intersected continuously with the Camp sensibility. Stars like Mae West, Marlene Dietrich, and Joan Crawford embodied Camp. Camp also acted as a communication tool for a marginalized group of people, a secret code to finding like-minded individuals. Chi Luu wrote about the linguistics of Camp commenting, “what better way to protect a private self than behind the safety of an over-the-top, ironic performance?”

Drag is of course a prime example of this, and of Camp. Susan Sontag talks about the Camp taste for both “the markedly attenuated” and “the strongly exaggerated.” Camp favours both androgyny and hyper-exaggerated femininity and masculinity. Sontag writes, “the most refined form of sexual attractiveness…consists in going against the grain of one’s sex.” Drag is about exaggeration (over-the-top looks and makeup), artifice (impersonation), and theatricality. Some queens are campier than others (looking at you Nina West), but the artform itself draws deeply from this well.

Many have criticized Sontag for her controversial stance on the politics of Camp. The second point of her essay is, “It goes without saying that the Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized -- or at least apolitical.” Although she names homosexuals as the “vanguards” of Camp, she says “yet one feels that if homosexuals hadn't more or less invented Camp, someone else would.” Preposterous! In discussing Camp linguistics, Luu writes, “What other subculture would have the drive and the expressive urgency to develop something as frivolously influential as camp? On the one hand, you have a socially stigmatized subculture in hiding, at risk of public exposure and abuse and, on the other, that same community’s fervent desire for theatrical, socially confronting gender-bending self-expression.”

While it may have started in queer circles, Camp has evolved significantly since Sontag’s essay. Modern Camp can be found in almost every discipline. A Widewalls Editorial even goes as far to claim that Sontag’s essay unlinked Camp from its queer history and “gave it a wider currency.” Warhol created a film called Camp in 1965, and the aesthetic began to show up in all sorts of art, film, and fashion. John Waters, the king of Camp, made Pink Flamingos in 1972. Camp informed the works of Cher, Bowie, Elton John, fashion houses like Chanel and Versace, Bjork’s famous Swan Dress, Lady Gaga’s meat dress, and a whole plethora of furniture, costumes, music, film, and art. Arguably, the campiest person today is in the Oval Office, with artifice adorning everything from his skin colour to his rhetoric.

Although Camp has become culturally dominant, it seems to have forgotten its original intention. Filmmaker Bruce Labruce condemned Sontag’s depoliticization of Camp, lamenting that its infusion into mainstream culture has diluted its power and significance. Without its original context, Camp has been separated from its roots in rebellion, survival, and subversion. Historically, I see Camp as a way in which those who were “othered” could play with the boundaries and rules of the very structures that they excluded from.

Today, the Met Gala guest list doesn’t reflect that sentiment. Wintour confirmed that RuPaul will be attending, and we might see Bob Mackie and Cher. Lena Waithe plans to honour the New York ball scene. “It all began with the black queens in inner cities looking for a way to be themselves, and then the culture got co-opted, so I really want to pay tribute to them. I think we might play with color and really lean into the drama.” The Ball scene demonstrated that Drag wasn’t just about gender, but about impersonation, embodiment, and performance.

So far, that gives us three LGBTQ members at the gala. I’m a little disappointed, although we’ll have to see for sure tonight. With Shangela anointed by Queen Bey, Trixie running an empire, and Willam at the SAG Awards, Camp at the Met gala would have been the perfect year to have Drag Queens on the committee. Sasha Velour could dress circles around the committee members.

I’m still very excited to see what my faves will wear tonight. However, with regards to the theme and the overall history, I think the host of the So Fashionating podcast, Ruby McCollister, sums it up best. “A dress can be campy but only fully animates itself on a person that embodies its psychological illness of 'being' camp… This Met Gala is gonna be so fabulously bizarre because all these blandos are going to be wearing these clothes, vestiges, shorn skins of someone’s outrageous, compulsive psychology. Crazy. That dichotomy: the pedestrian wearing the deranged…hell…that's camp.”

So as we celebrate the indescribable sensibility of Camp today, let’s try remember its roots as well.

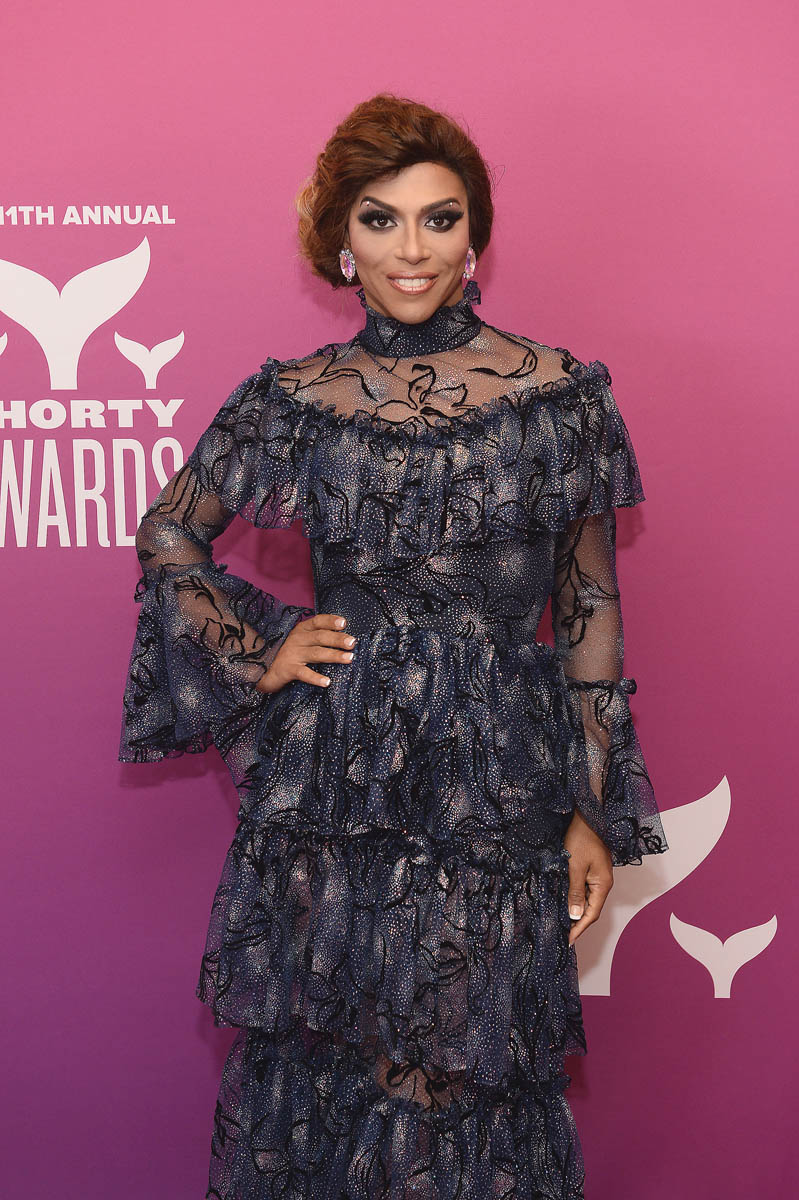

Attached - Shangela at the Shorty Awards and GLAAD Media Awards on the weekend.